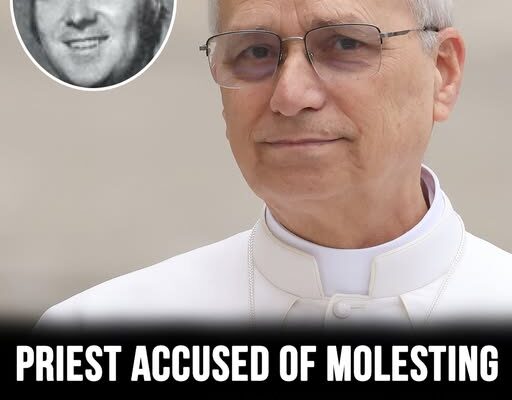

Just weeks into his papacy as Pope Leo XIV, Robert Prevost faces a scandal that could shake the very foundations of the Church. A defrocked priest from the Chicago area has come forward with explosive claims: Prevost, before becoming pope, personally authorized the priest’s residence at a monastery in Hyde Park — located mere steps from an elementary school — despite full knowledge that the priest was accused of molesting children.

Living in the shadow of a school

James M. Ray, a disgraced former priest, revealed to the Chicago Sun-Times that Prevost, then leader of the Catholic Church’s Augustinian order in the Midwest, signed off on his stay at St. John Stone Friary from 2000 to 2002.

“He’s the one who gave me permission to live there,” Ray stated bluntly. What makes this revelation even more shocking: Ray had already been accused of abusing at least 13 children and was supposed to be under strict restrictions. Yet, he lived less than a block away from St. Thomas the Apostle Elementary School — a fact that was never disclosed to the school community, leaving parents and staff in the dark.

According to the Chicago Sun-Times, official Church records initially denied any school existed near the monastery — a claim now definitively disproven. In reality, a child care center sat just across the alley, yet neither parents nor staff were ever informed of Ray’s presence.

“The Augustinians were the only ones who responded when the Archdiocese sought housing,” Ray asserted, dismissing rumors that the Archdiocese pressured the order to take him in.

Was Prevost aware of this arrangement?

While the Archdiocese—not the Augustinians—held ultimate responsibility for Ray as one of its priests, no law apparently mandated informing neighbors about an accused abuser living nearby.

Still, a formal complaint alleges that Prevost was fully aware of this arrangement, citing a 2000 internal Archdiocesan memo, and argues that he should have alerted the school.

In response, a lawyer for the Augustinians maintains that Prevost simply “accepted a guest of the house,” placing oversight responsibility on the friary’s onsite monitor, the late Rev. James Thompson, who was tasked with supervising Ray.

Ray was finally removed from public ministry in 2002, following the groundbreaking Boston Globe investigation that exposed the Church’s widespread cover-up of abuse scandals. A decade later, in 2012, he was defrocked.

“I felt abandoned by the Church, but never abandoned by God,” Ray reflected. “My faith remains strong. I try to live each day the best I can. But when this comes up, there’s a pain deep in my chest.”

Despite numerous victims — some as young as 10 years old — Ray downplays the allegations:

“It was a young man I gave back rubs to,” he told reporters. When pressed for details, his answers grew vague and confused, ending with a simple, “I don’t know.”

“Silence is not the solution”

As the Church continues to confront its painful legacy, Pope Leo XIV has publicly vowed transparency and healing. In 2023, after assuming his Vatican role responsible for appointing bishops, Prevost told Vatican News that while some bishops have made strides in addressing abuse cases, “more support is needed for bishops who have not received the necessary preparation” to handle these challenges.

He stressed, “Silence is not the solution. We must be transparent and honest. We must accompany and assist the victims, because otherwise their wounds will never heal.”

Yet, this explosive revelation raises urgent questions about what occurred under Prevost’s leadership as a senior Augustinian. To be clear, the pope himself has never been accused of any abuse.

When asked about Prevost’s rise to the papacy, James M. Ray quipped, “Why did it have to be an Augustinian?” But beneath the humor, Ray admitted Prevost’s appointment sends “very positive vibes.”

Ray also hinted that he is not the only controversial figure from Prevost’s past — suggesting others remain hidden in the shadows. For a Church desperate to move forward, the long, dark shadow of its past may yet linger.